Blocked from knowing my history, a product of the Baby Box theory, I only remember the love of one family. It wasn’t the choice of my adoptive family (or what I will refer to as “my family” in this post) to keep me from my first family. The members of my family believed for all legal purposes that I was an orphan that became their daughter and sister.

I have very fond memories of my family. As I sit in Seoul, peeling chestnuts and eating them raw, I remember the chestnut orchard of my grandfather. I would hang and swing from the branches of those mighty trees in the fall weather of East Tennessee. It was idyllic and comforting. I loved breaking apart the prickly pods to reveal the raw meat of a nut no one else loved as I did …

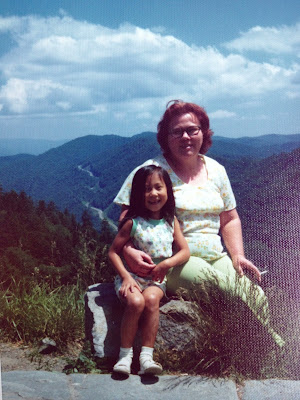

In Seoul, I bought a bag of corn chips, much like the Bugles my grandmother bought for me from the vending machine where she cleaned rooms at the local hotel. My family’s life was simple. We lived simply, just as I imagine my first family did. It seems fitting that I would become the daughter of a set of parents who grew up poor as well.

The days of reminiscing with my parents are gone. My mother passed just as I was becoming the mom she had taught me to be. For years, I struggled with the loss of her.

My father and sister stood with me when my mom died. Their grief was mine and mine, theirs. We spoke among ourselves about her impact on our lives. I shared with them the pains of feeling alone in my parenting.

My younger sister would soon have a little one of her own. Feeling comfortable with infants (after having my two), I cherished the time spent with her as she struggled to wrestle motherhood to the ground. One day, she said, “You have done the very thing that would have made Mom so very proud.” That was a golden moment in my life. I was “Mom.”

My younger sister would soon have a little one of her own. Feeling comfortable with infants (after having my two), I cherished the time spent with her as she struggled to wrestle motherhood to the ground. One day, she said, “You have done the very thing that would have made Mom so very proud.” That was a golden moment in my life. I was “Mom.”My father’s family became the strength in the lives of my children as they grew up only really knowing my father and not my mother. We made many trips to Puerto Rico to connect. They feel they are Puerto Rican.

But our time with my father was also fleeting. His death this last January was a blow we never imagined at the time. He had been my link to Korea … his time there, his love for the country and his honest interest in my original family search. He was my supporter when the world’s eyes saw me as a disloyal adoptee.

In the following months, I would learn more about my father’s time in Korea and his short love affair that resulted in a son … a man only one year older than me and the physical embodiment of the identity I had spent my entire life building.

What I wish adoptive parents would consider is that once they pass on, the adoptee is truly alone. We are left with a family that is only ours by association. In my case, my extended family works to stay connected, but deep down, I feel separate. My children and I long for a connection to the one man who embodies my father and my biological Korean side.

My writing is not for my late parents. My writing addresses me as a person, a mother, an adoptee, my parents’ daughter, my original family’s lost daughter and as the foster child to a foster mother I can only see in faded pictures.

Feminist columnist, Rosita González is a transracial, Korean-American adoptee. She is married to a Brit and is a mother to two multiracial children. Rosita was adopted in 1968 at the age of one through Holt International. Her road has been speckled with Puerto Rican and Appalachian relatives and her multiracial sister, the natural child of her adoptive parents. While quite content with her role as a “Tennerican,” her curiosity has grown recently as her children explore their own ethnic identities. She considers herself a lost daughter, not only because of the loss of her first family, but also because of the loss of her adoptive parents. After her adoptive father’s death, she discovered that he had fathered a Korean son two years before her birth; she is searching for him. Rosita is currently living in Seoul, South Korea with her family and their three cats. Follow her adventures as an adoptee on her blog, mothermade.